Palmer-Taylor Power Station, Los Santos, Grand Theft Auto V

Still from Plastic Scoop film Machinima, 2018

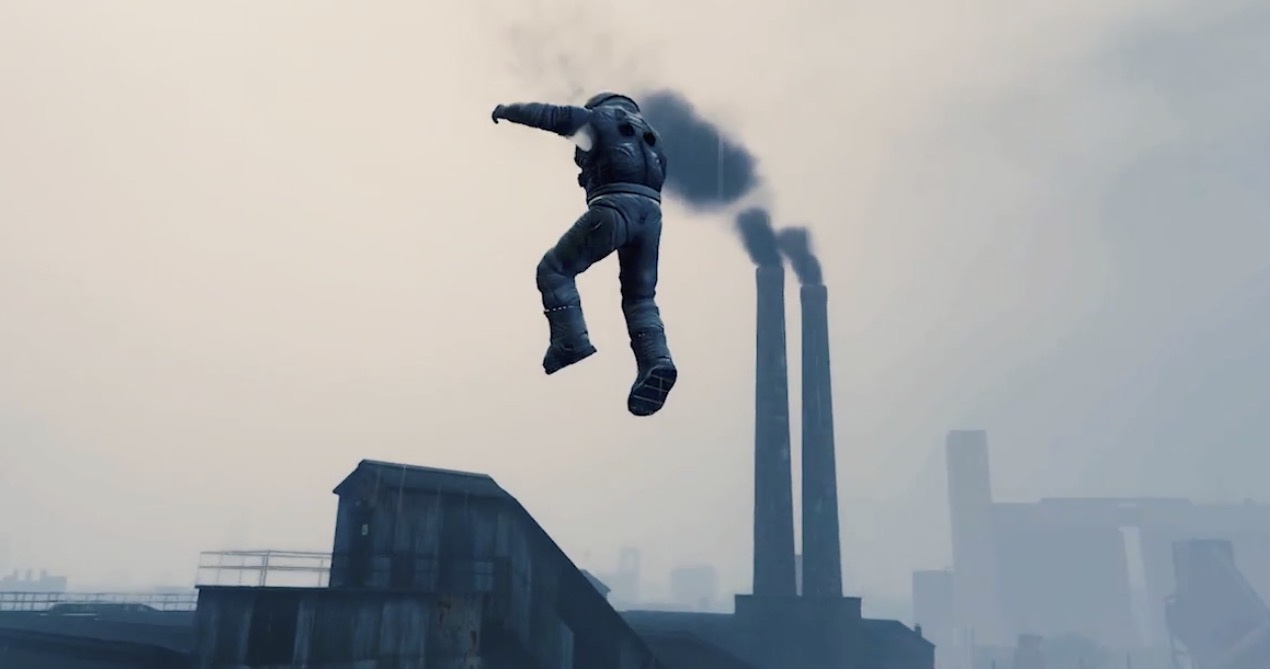

Falling to earth above Los Santos, Grand Theft Auto V

Still from Plastic Scoop Film Machinima, 2018

Palmer-Taylor Power Station, Los Santos, Grand Theft Auto V

Still from Plastic Scoop film Machinima, 2018

Falling to earth above Los Santos, Grand Theft Auto V

Still from Plastic Scoop Film Machinima, 2018

The film features gleaned archival material and cinema footage from early exploration, NASA and with his own recorded and directed in-game machinima. Grand Theft Auto V is one of the most popular video games of all time, played by millions across the globe, it has generated many controversies related to the game’s known themes around gang violence, car theft and racial stereotypes. With the release of each new version of GTA Hughes noticed how changes in the rendering of the game of both the seascape and landscape seemed to mirror wider societal awareness of pollution issues such as plastic waste and global heating. Could the increasing presence of trash, other visible pollution and traces of climate change discourse (and its denial) within the game be potentially concealing a series of environmental messages ?

Astronaut, Grand Theft Auto V

Still from Plastic Scoop film machinima, 2018

Sea Anemone, archive footage

Still from Plastic Scoop film machinima, 2018

Archive footage, US Navy

Still from Plastic Scoop film machinima, 2018

Diver with gun, Grand Theft Auto V

Still from Plastic Scoop film machinima, 2018

The sea in this poem has often been read as metaphorical for universal human travails, but its redeployment here suggests a different perspective on the poem, which now offers prescient visions of the ocean as a non-human multispecies habitat, but one that also ‘tosses up our losses’ in the form of a variety of human waste.

As with collage work more generally, then, the juxtaposed materials transform one another through strange forms of connection and disjunction. Through such transformations, Plastic Scoop forges links between industrial and post-consumer pollution, production and waste, and, perhaps most importantly, acts of violence and the logics of capitalist production and consumption. In strange and uncanny ways, the film reveals violence in all its multifarious forms as endemic to a capitalist system reliant upon unequal relations of power, the ruthless exploitation of the natural world and human labour, and the transformation of physical and mental spaces into arenas of domination and individualist competition.

A bizarre set of characters roam this virtual world; an aeronaut emerges from the sea, a diver roams a highway shooting at signs promoting climate change denial, and a clown writhes in mid-air, accompanied by whale song. These are alienated figures, struggling to function meaningfully in the environments in which they find themselves. The film often takes their perspective, sometimes situating itself literally inside their cranial cavities. Through these characters, the strange but frighteningly familiar landscapes they move through, and the competing discourses that surround them, the film raises a host of questions, such as: How have we come to normalise the environmental mess that we now find ourselves in?

How might we perceive our world differently than we currently do? How can we thread a meaningful path through the tangle of environmental discourses of our times, without succumbing to either apocalyptic fatalism, escapism or unrealistic optimism? It is not the task of art, of course, to offer solutions to such dilemmas. But if Plastic Scoop leaves its viewers with an disorientating image, an unsettling question, or even just a needling sense of disquiet, so much the better.

© Mandy Bloomfield 2019

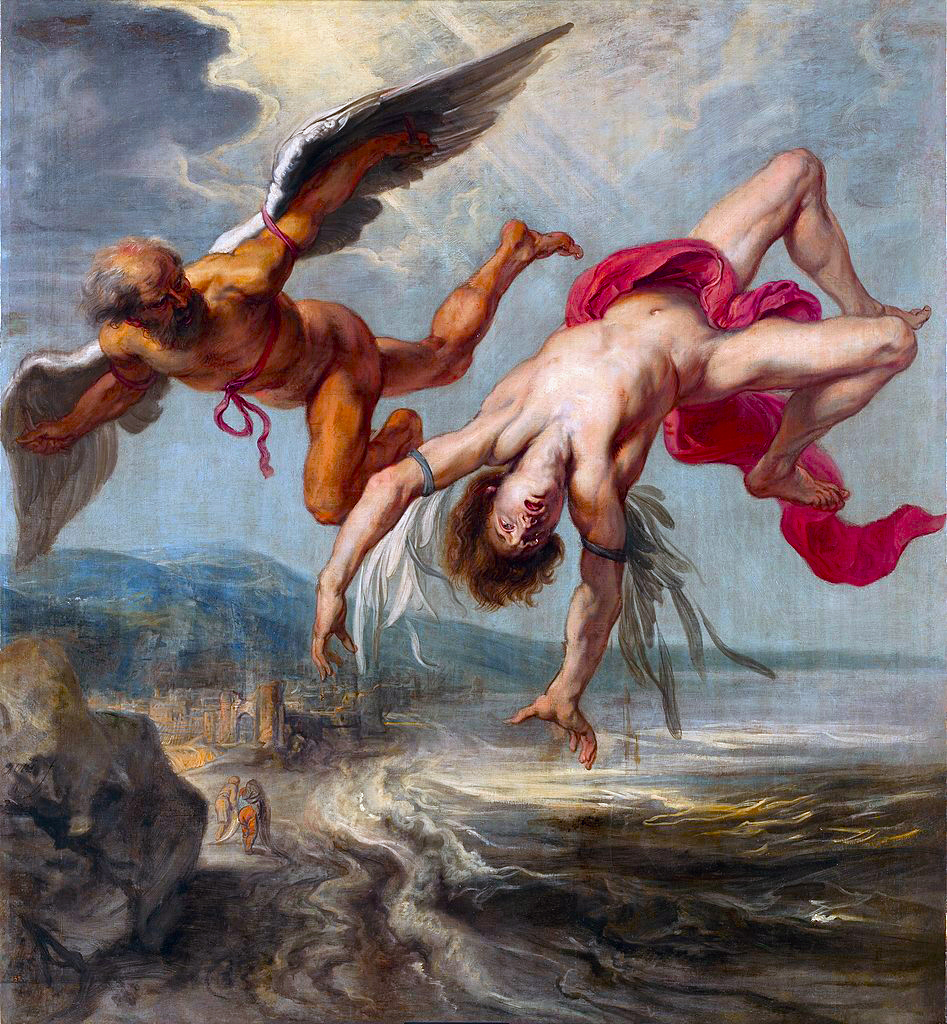

Jacob Peter Gowy, The fall of Icarus, 1637

Oil on canvas, 195 x 180 cm, Madrid, Prado Museum

For Icarus by Elizabeth Perrotte

Program Director, Christies Education, London

‘Time and space dilate; a mysterious avatar free-falls, slowly, hypnotically, out of a clear sky,’ haloed as he gently spirals away from the dazzling sun. For an occult moment the boundless air becomes a deep ocean for his fall; a whale’s soundscape of low groaning vibrates through the visuals. Thoughts of Icarus accelerate the vertigo. Fragments of his mythic flight and plight; fragrant wax wings melting in the sun’s heat, fast flicker into view. This Icarus plunges from the blinding sun into rich technicolour dressed as Pierrot, the androgynous, melancholic clown from Commedia dell’arte. Suspended here in limbo between states: powerless yet vagrant, symbol of free will, escape, jouissance, hubris, collapse, catastrophic failure, so much waste matter. No ground in sight, impact deferred, there is always the hope of ‘clinamen’ the chance atomic swerve and generative energy celebrated by Roman poet/philosopher Lucretius in De Rerum Natura (The Nature of Things).

If atoms never swerve and make beginning

Of motions that can break the bonds of fate,

And foil the infinite chain of cause and effect

What is the origin of this free will

Possessed by living creatures throughout the earth?

Whence comes, I say, this will-power wrested from the fates, Whereby we each proceed where pleasure leads,

Swerving our course at no fixed time or place

But where the bidding of our hearts directs?

For beyond doubt the power of will

Acknowledgements

Dr Mandy Bloomfield and the Sustainable Earth Institute (University of Plymouth) deserve deep thanks for their generous support of this project, as does Lizzie Perrotte, whose viewing of the film was both helpful and inspiring. Thank you to the University of Plymouth English students who responded with perceptive observations about the film and through interactive game sessions changed my course of thinking about the film and its narrative/non-narrative potential. Thank you to Dominica Williamson (ecogeographer) who reminded me throughout the production to think about audience and co-production elements. Thanks also to those people online who commented during production and also to Alison Wallace at Truro-Penwith College who offered technical advice. Film Project Funded by Sustainable Earth Institute at the University of Plymouth.

The Sustainable Earth Institute’s Creative Associate Awards are designed to uncover novel and innovative ways of communicating research to a public audience. The awards have been made possible through funding from the University of Plymouth Research Impact and Innovation Fund, which is financed by the University’s Higher Education Innovation Fund (HEIF) allocation

For further information about the Sustainable Earth Institute and the University of Plymouth

No Code Website Builder